To view our Privacy Policy please click below

Supporting the North West Centre for Heart & Lung Transplantation

Bill Noble’s Dickensian Approach

Mr Micawber from ‘David Copperfield’ by Charles Dickens.

‘Remember my motto, Nil Desperandum! -Never despair!’

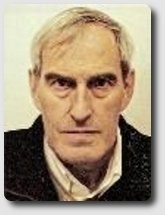

Bill Noble photographed in October 2006, about 6 months before his heart transplant. With all due respect Bill, it looks like you had just received another shock from your defibrillator (ICD) to get your heart going properly.

“Life can’t get any better, can it?”

It now feels almost surreal as I look back over my life of sixty years; the past forty of which have seen me struggle through countless crises managing my heart rhythm problem, the past fourteen with an implanted defibrillator (ICD); five in all each one more sophisticated than the last. The countless visits to Coronary Care, Intensive Care, Catheter Labs., the numerous hospitals, here and overseas and ambulance rides; the therapy and all the drug trials. Looking back I’m reminded of all the incidents along the way, some funny, many traumatic and when everything was stable for a time and life was good.

That’s the way it was, taking a few steps forward and a few steps back, but never an answer, never a fix. I would be less than honest if I did not admit to periods of anger and wanting it to go away, just to stop; the thought ‘why me’ was an irregular, but constant companion. But I knew deep down that there was no answer, no fix, just the hope that when I had to confront the next crises something would come along to keep me going such as a new drug or a new machine; I call it the Mr Micawber view of life (from the character in Charles Dickens’ novel ‘David Copperfield’). Whilst it may appear a somewhat flippant philosophy it has served me well because, against all the odds, something indeed always did come along.

I was a competitive swimmer and at the age of twenty my heart stopped when I was in the water in a race. That would have been the end, but for the fact that all my team mates were experienced competition lifesavers and first aiders who immediately diagnosed the problem, got me out of the water and restarted my heart; my first ambulance. Not that anyone recognised the underlying congenital problem at that time this episode being diagnosed as exhaustion caused through over training; so just a blip then and nothing to worry about!

Over the following years when I had periods of feeling disorientated and generally unwell I just accepted them as nothing more than part of the body’s reaction to high levels of physical activity. In 1976 at the age of twenty nine whilst playing squash the lights went out again. It is not certain if my heart stopped, but the possibility is that it did, however apparently I hit the floor so hard onto my face and chest that the impact would have restarted it. This time after being stitched up in A & E and returning to see my GP I was hospitalised and put through a whole barrage of tests, but again I was apparently in the prime of health!

That was the turning point and things gradually deteriorated towards the end of that year resulting in me have to call on medical assistance time after time. One night, when my own GP was on holiday, was particularly traumatic so I was visited by a locum GP who suspected he might know what the underlying problem could be. However, he could not make a diagnosis, but he knew a man who may be able to; that man was Dr Geoffrey Howitt a consultant cardiologist at Manchester Royal Infirmary; apparently he had a new machine called a catheter. So hospital again; my first catheter lab with the shocks and dyes and funny pictures on a TV screen. After a week of tests I was informed that they thought they knew what the problem was, but could not make a definitive diagnosis, but knew a team in London doing research that may be able to do so, if I was willing to join the programme! I joined.

A few weeks later I found myself acting as a guinea pig in Hammersmith Hospital to a research team working in electrophysiological studies led by Dr Edward Rowland (Ed). After another barrage of tests over two weeks back and forward into the catheter lab, wired up on running machines and exercise bikes I finally found myself half conscious hanging in a harness, my nose about a foot from the floor with a team of doctors in white coats, looking at a barrage of machines, shouting ‘eureka’; the answer? No matter that I felt as sick as a pig and was shaking all over I felt, for a brief moment happy, but thank god for anaesthetic and cardioversion.

The diagnosis, Right Ventricular Tachycardia, but what to do to treat it? After a number of trials with drugs I was finally prescribed Quinidine and this appeared to work well for a number of years with some tinkering in between, but inevitably I was back having attacks, having to go into hospital and be cardioverted.

Again, when I had a desperate need to have help close at hand that was available through circumstances where, by chance, I was living less than a mile from a coronary care unit and a hospital specialising in coronary heart disease. Whilst Rochdale Infirmary at that time did not specialise in electrophysiological studies the consultant, Dr Mick Coupe and later Dr Mark Hargreaves, together with their team were well informed of my specific problem and without question saved my life on a number of occasions. The kind of care I received, and continue to receive from them, made me aware of another important part of caring and that is, whilst clinical excellence is paramount so too is the reassuring personal touch that patients need when at their lowest point. For example to be told by very busy consultants – ‘don’t worry about appointments if you need me just come and see me’ – provided a peace of mind that helped me manage my condition over the years.

There then followed different combinations of drugs, the principal being amiodarone. Whilst they worked for a time, the gap between attacks was becoming less and less to the point where during 1992/93 the attacks became more severe and I was ending up in CCU and being cardioverted on a regular basis.

From the time I first went to Hammersmith Hospital I was supported by Dr Rowland and was treated by him and his team through a number of London hospitals, finally ending up at St George’s Tooting. In early 1994 I was informed by him that the drug therapy had been exhausted and that there was a strong possibility that I would soon not make it to hospital to be cardioverted, but there may be help; would I be willing to be fitted with an ICD. I think I agreed even before asking what it was! When I found out it would involve having a box in my stomach, wires fed up to and attached to my heart and the surgery that involved I was taken aback, but if it had the potential to save my life then there was no choice; another Mr Micawber moment! Another one was soon to follow.

A month later after the finance had been agreed with my health authority; I was informed that there was a new device that could be implanted under the skin in the upper chest, much like a pacemaker, but that they were big! When I was told that it would involve much less radical surgery I didn’t care how big it was, that was the one for me. So I now had my own personal lifesaving defibrillator. Little did I realise how pioneering this procedure was. I knew I was one of the first to be fitted with this new type of device, so it became newsworthy and the operation was recorded followed by interviews; just look how far have we have come now! Do I want to see the video of the operation asked Ed? Very kind, but no thanks!

After this, when I was taken to a hospital where no one knew me or they were not familiar with ICD’s, I had to spend time convincing them that I really had a defibrillator inside me. Looking at my lump and the size of their defibrillator on the trolley ended with looks as if saying – ‘he’s bonkers’ and enquiring if I banged my head when I collapsed!

In 1997, as ICD implants became more common, smaller and more sophisticated, I was transferred to the care of Dr Adam Fitzpatrick and the team at Manchester Royal Infirmary. The box was replaced four times, the fifth and last one in April 2006 being particularly traumatic for my family when, during the procedure my heart stopped for twelve minutes and could not be started using the external defibrillator. But a period of external cardiac compression on the floor finally got it going again! By this time life was becoming more and more difficult and I was able to do less and less. Whilst the ICD had kept me alive during numerous attacks over the years each experience was becoming more and more unpleasant and the recovery period longer and longer, but one just had to grin and bear it!

I had joined the police service in 1964, but at the end of 1998 I had to stop working as my health continued to deteriorate and I was required to surrender my driving licence because some attacks rendered me unconscious. As my job as a Detective Superintendent involved a 24/7 responsibility, working long hours, being called out at anytime, the loss of my licence and deteriorating health made it impossible. But again there were periods when things were fairly good and it was possible to think that ‘if it stays as it is then it won’t be too bad’, but of course it never did; a little way along the road another crisis.

By October 2006 things were pretty dire, as the photograph clearly shows; not only the arrhythmia, but congestive heart failure. No more machines and no more drugs! It was at this point that Mr Micawber comes along again when I am asked to consider the possibility of a heart transplant. My first reaction was, heart transplant, aren’t they for very sick people? It’s difficult to comprehend, but it is only now looking back that I realise how little we sometimes understand about our personal situation. Having been used all my life to getting over difficult times it’s easy to get into the mode of thinking that things will get better.

From this time on I spent a considerable amount of time in one hospital or another and in January 2007 went to the Transplant Centre for assessment. On 17th April I received a new heart, a gift beyond all imagination.

It has transformed my life and that of my family beyond anything previous. I have been given my driving licence back; oxygen cylinders do not have to be carried about; there is no need for someone to be with me twenty four hours a day; I am not waiting for that shock every time I feel a bit disorientated; the cold sweats at the prospect of doing some task that will possibly cause an arrhythmia attack or gasping for breath trying to walk up stairs. In fact I can’t think how long ago it was that I felt this good about life, wanting and being able to do things again, but who cares, there is nothing more important in life than life itself so I just get on with it and don’t worry about things over which I have no control.

I have been a churchman all my life and a churchwarden for many years and have always had hope and faith whenever in a crises. Sixty years on when, but for timely interventions I should not be here, God and all the medical teams are still pulling me through; and like Mr Micawber I too –“have every expectation that (when the need arises) something will come along” – ‘life can’t get any better can it?’

Bill Noble

BIll receiving an award at the 2014 games in Bolton